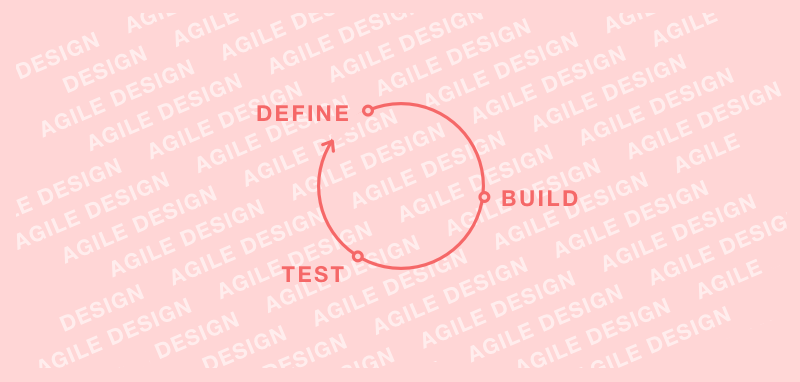

Agile Design

I've taken inspiration from Google Ventures 5-day sprint and Atlassian's Agile Coach, but I’ve often wondered about how to define an “iteration” and how long should each iteration take.

In my practice, my process has evolved depending on the needs of the project and team. Here I outline step-by-step my own interpretation of agile and iterative design.

Iteration 1

DEFINE

Bring in a diverse team with members representing business goals (like PM, sales, or marketing), the users’ voice (like designer, CS, or account manager), and the technical capabilities (like engineering or QA). This team will determine their confidence level in the new information presented. A simple way to think about it is in these 3 buckets:

√ Truths - or the things we are confident enough to move forward and build

? Unknowns - or gaps in the existing research that need further investigation

X Out of Scope - or extraneous features that distract from the core objective

BUILD

At this early stage in a project, it’s likely that we don’t know enough yet to start designing or developing anything, so let’s skip this step for now and move on to uncovering unknowns.

TEST ASSUMPTIONS

For large (and risky) projects, mostly everything needs to be validated, i.e. “How users behave and what challenges they face?” Consider who can answer these unknowns and what method will get you answers. For a deep discovery into user behavior, you can shadow or ask research subjects to keep journals. For a more hand-on approach, you can facilitate card sorting or journey mapping workshops. Perhaps there are SMEs in your company you can interview. (IDEO offers tons of great methods).

Whichever format you use, be sure to outline research objectives, materials (i.e. script, prototypes, office supplies, etc), and logistics (i.e. recruiting and scheduling participants / proctors / scribes, incentives, database to organized information, prototypes / scripts, etc). There’s too much to cover in this article.

Iteration 2

REDEFINE

Once you’ve conducted the first round of tests, synthesize data and share new info with your team. I’m partial to fancy tools like Airtable for capturing insights, but a good ol’ spreadsheet will suffice. Next, level up your research by creating personas to get into the mindset of your users and journey maps to help identify the problem areas. And again, classify this new information.

√ Truths - We understand various pain points along the user’s journey

? Unknowns - What is the most prominent pain point and what will solve that problem?

X Out of Scope - Speaking with users will generate an abundance of ideas, but remember to keep the focus. We can always explore these ideas at a later time.

BUILD

Identify the biggest problem area in the user’s journey and sketch possible solutions to the problem. This needs to be a multidisciplinary team effort. Remix and combine solutions, choose the best and start building a prototype.

TEST CONCEPTS

It’s still unclear whether these concepts actually solve the users’ problem or how willing users is change their existing workflow to use this new solution we’re proposing, so I meet with users and and get feedback early. Additionally, it’s important to ensure these concepts are technically feasible and aligned with business goals. I meet with engineers and product managers to hash out these questions.

Iteration 3

REDEFINE

Share, classify new insights. Did the test results validate or contradict our hypotheses? Correct course when necessary, even if that means taking a step back or “throwing away” work. Get feedback early and often so we don’t invest too much time in a bad idea.

√ Truths - We’ve generated promising solutions and chosen the strongest ones.

? Unknowns - But now, is this solution design in the best way?

X Out of Scope - Keep documenting new ideas that crop up. This becomes the backlog of new research questions to uncover.

BUILD

Move ahead on what we know to be true. Continue refining wireframes / prototypes to a higher fidelity. Engineering can start on implementing a framework. Design should be about a week or two ahead of engineering, but both disciplines are working closely in tandem.

TEST USABILITY

We need to uncover whether the designs self-explanatory such that users can do such-and-such without confusion. As the designs get more detailed, we test info hierarchy, flow, terminology, UI affordance, and accessibility by creating an interactive prototype and asking users to complete a set of tasks.

Iteration N

REDEFINE

This article illustrates only a few iterations, but in reality it could take dozens of iterations. You may find yourself starting back at square one if your tests show that you’re headed in the wrong direction.

√ Truths - Hopefully at this stage the team is feeling confident they’re delivering a solution that’s valuable and easy to use.

? Unknowns - There aren’t unknowns we can test in a fake environment, so it’s time to test how this feature performs in the real world.

X Out of Scope - Along the way, we may discover some features we feel confident about. We can queue them up for Phase 2.

BUILD

Design is refining the product, fleshing out edge cases, ensuring experience on brand, adding animations / transitions, and writing UI copy. Engineering is finishing implementation and preparing for release. Other disciplines are also springing into action: Marketing is queueing up an announcement, CS has been trained and is prepared to train clients, etc.

TEST IN THE REAL WORLD

How will this product be received in the real world? What are the success metrics? Who are the users we test with? How many to we roll out to? How long do we gather data until we feel confident enough to roll out to more users?

Now here's where my struggles and learnings come from. I outline my experiences from my past two product design roles.

Experience from Namely

In the early days at Namely, we were far from perfect. I didn’t know any better than to design high-fidelity specs for a feature and hand them over to engineering. What’s worse was that engineering couldn’t implement it for another 6 months because they were tied up with another project. We didn’t know at the time but this other project ended up taking 9 months to build.

We didn’t estimate or try to cut down the scope of a project, so we didn’t know what we were committing to. This tremendous lag between design and implementation made it impossible plan ahead. We were stuck in a waterfall cycle and couldn’t sync design and engineering stages together. By the time engineers were available to build, either the scope changed or it was decided to abandon the project entirely because of shifting priorities, which caused people to distrust the roadmap.

(And on top of all that, we weren’t conducting user research or prototyping back then, which made these projects even riskier! But there’s too much to cover in this article.)

Solution (Part 1)

In 2016, an agile consultancy came to jumpstart Namely’s budding project management department as well as to train engineers on this new framework.

Goals:

Improve visibility around feature teams and their progress

Provide predictability in costs, schedule and delivery

Encourage ownership and facilitate collaboration

The consultants worked with project managers and engineers to accomplish these major tasks:

Established JIRA as the central tool for all project management. (Previously we used Trello, Asana, and Aha.)

Created JIRA boards for each feature team.

Defined each stage of development (from “Backlog” to “Done”) along with channels to raise flags and change course.

Explored frameworks for writing and estimating tickets.

Scheduled 2-week sprints with backlog grooming, sprint planning, retros, and daily standups.

These were huge improvements for the engineering team, but this plan didn’t cover how to incorporate the product and design teams into this process. It assumed an engineer’s involvement starts when the backlog is populated with stories and final designs. This was only the first step away from waterfall and towards a more agile workflow.

Solution (Part 2)

As a designer working on 3 different features at a given point, I was eager to get my work integrated into this new process. In addition to the company’s goals outlined above, I had some selfish goals:

Clear Priorities - When priorities compete, asking a stakeholder to order the backlog will get me answers.

Reasonable Timelines - When faced with aggressive deadlines, this framework helps me communicate what’s a more reasonable deadline for this amount of work, or what’s a reasonable workload for this timeline.

Accountability - I can hold myself accountable for my work, as well as, hold others accountable for unblocking my work.

Predictability / Flexibility - Committing to work in a sprint allows for some predictability each week as well as some flexibility beyond that.

I collaborated with the Design Manager, Head of Product Management, and Project Manager to build a workflow for design and product that works in parallel with engineering’s. Ideally, design shouldn’t be more than 1 month ahead of implementation, so we’d use the same ceremonies and JIRA boards to plan design tasks alongside engineering tasks. But because there was still a huge lag, here's the solution we found in the interim.

We captured design and product tasks in JIRA tickets.

If we had tasks that were closely related to what engineering was currently building, those tasks lived on the feature teams’ boards.

For tasks that wouldn’t be built until further out in the future, we created a new "Product & Design" board (to avoid cluttering the feature teams' boards with "irrelevant" tasks).

We attended engineering’s ceremonies facilitated by project managers, but for our "Product & Design" board, we were each largely responsible for estimating tasks, ordering the backlog, and organizing sprints ourselves.

This new process gave the rest of the organization visibility into product and design work, but product and design's workflow was still separate from engineer's (as characterized by having multiple boards). There’s still more to be done to make the interdisciplinary processes more collaborative.

Experience from Clark

Having a 6-month lag between design and implementation at Namely wasn’t ideal. On the other end of the spectrum, being the sole designer at Clark trying to keep up with 4 in-house engineers and 2 contractors wasn’t ideal either. Other issues include:

Each iteration should have produce learnings, where the team may decide to change course, which leads into this next bullet point.

There was a breakdown in communication. I could have done more, of course. But it was challenging to balance how we communicating decisions AND how we democratically make decisions. In terms of merely communicating, there seemed to be an expectations of highly polished presentations given the company's history of working with outside agencies.

What's in scope? As a designer, I fully embrace my role to push the envelope and fight for a more enriching experience for the user. Some call that "Scope Creep."

Blurry deliverables (since “final designs” will take who knows how long). I could have outlined more specific and achievable deliverables, such as “User Flow for Error State,” “Wireframes for Happy Path,” “Usability Tests - Round 1, 2, 3…etc”